Night Voyage to Spitsbergen

A few years ago, I spent a fortnight traveling by ship around the entire Spitsbergen archipelago, and although I wasn’t then thinking about ghosts, I was so struck by the beauty and the desolation that I knew I would at some stage write a story about it.

A few years ago, I spent a fortnight traveling by ship around the entire Spitsbergen archipelago, and although I wasn’t then thinking about ghosts, I was so struck by the beauty and the desolation that I knew I would at some stage write a story about it.

My first trip was in summer, at the time of the midnight sun, and Jack’s experiences on first seeing Spitsbergen are mine: the sinister, black-faced polar bear who’d been eating the walrus from the inside; the abandoned guillemot chick; Jack’s solo walk to the small, cold lake; and those brief but desperate moments when he thinks he’s lost… All this is what I’ve seen and experienced myself.

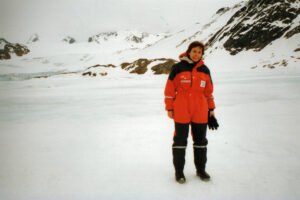

Getting the feel of the sea-ice at the foot of a glacier. Kulusuk, East Greenland

While I was writing Dark Matter, I needed to get the feel of the polar night at first hand, so I went back to Spitsbergen in winter. I went snowshoeing in the dark (with and without a headlamp), and climbed a glacier in driving snow and zero visibility. It was the time of the full moon, and because I was living Jack’s story in my head, I realized how paranoid he would be about the least shred of cloud drifting across the moon.

Also, I discovered a curious thing while I was out hiking. Whenever I lagged behind a little, I kept hearing this strange “echo” effect: as if someone else in snowshoes were following me. Doubtless it was no more than the echo of my own snowshoes, but it was distinctly unsettling.

[pull float=”alignleft”]I got a sense of the unease you’d feel on entering a small, freezing cabin in the dark[/pull]One of the most striking things I gained from my winter trip to Spitsbergen was the sense it gave me of what the cabin would be like. I got a sense of the unease you’d feel on entering a small, freezing cabin in the dark. Even when you’ve got that first paraffin lamp safely lit, the unease remains, because you can’t see much of what’s outside, and the cabin itself is full of shadows. What’s waiting for you, just beyond the edge of the light?

As far as the huskies are concerned, I’d been dog-sledding before, in the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, and Arctic Finland, and I did some more on my trip to Spitsbergen in the winter. I also spent some time looking after the dogs: harnessing them, feeding them, and generally getting ideas for the characters of the dogs in the story. Isaak is based on two in particular, to whom I got very attached: a young one called Borealis, who, like Isaak, was very enthusiastic and vocal; and a slightly more experienced dog called Mirak, who padded along with us on a snowshoe hike, and acted as a sort of canine early warning system for polar bears.

[pull float=”alignright”]The dead stillness of the dark months; the feeling of menace… I’ve felt this feeling too[/pull]I’ve modelled the details of Jack’s expedition on several real ones that took place in northern Spitsbergen in the 1920s and 30s, in particular on the Oxford University Arctic Expedition 1935-6. This was a year-long expedition involving ten men and twenty-three huskies. Much of the day-to-day details – the journeys to and from Tromsø, the gear, the provisions, meteorology, wirelessing, dogsledging and hunting – are based on this. They really did set off armed with Crown Derby crockery and cutlery from Mappin & Webb, along with fur motoring rugs and bottles of Heidsick Champagne for Christmas. But they were tough, too, putting up with temperatures of minus thirty below, dressed in little more than waterproofs and Jaeger wool.

In addition to this expedition, two other sources proved invaluable: the first was “A WOMAN IN THE POLAR NIGHT”, an account by a redoubtable trapper’s wife, Christiane Ritter, of her winter in northern Spitsbergen. The second was “THE DIARY OF THORLEIF BJERTNES”, an even tougher Norwegian trapper who overwintered with two companions in 1934-5.

It’s remarkable that in all these accounts – the Oxford Expedition, Ritter, Bjertnes – there’s repeated mention of the uncanny effect of overwintering in Spitsbergen. They talk of the dead stillness of the dark months; the feeling of menace; and the sense of otherworldliness and creeping unease. I’ve felt this feeling too. It’s the feeling you get when you’re far from camp, and not quite sure how to find your way back. When the mountains loom suddenly large, and you get the uneasy sense that you’re being watched; when your mind creates images you’d rather not confront.

It’s this feeling that prompted me to write DARK MATTER.